Editor’s note: Ezra Galston is a venture capitalist with Chicago Ventures and the former Director of Marketing for CardRunners Gaming. He writes the blog BreakingVC.

Editor’s note: Ezra Galston is a venture capitalist with Chicago Ventures and the former Director of Marketing for CardRunners Gaming. He writes the blog BreakingVC.As an investor in many digital marketplaces (Kapow Events, Spothero, Bloomnation, Shiftgig, among others, as well as an arts and crafts community, Blitsy) I have been eagerly awaiting Etsy’s S1 filing to get a deep look into the business.

The filing didn’t disappoint. Etsy is a powerful business with extraordinary network effects. Its customers are extremely loyal, and its committed sellers are earning significant income. But there are legitimate concerns: it is the quintessential case study on the challenge of low margin platforms. Additionally, it faces uphill challenges – a slowing growth curve and unclear product pipeline. Most importantly, the IPO comes at an inflection point as Etsy looks to expand from its niche, artisanal focus to serving a much wider market.

Let’s dive in.

Sizing up the space

To truly understand Etsy, I felt it important to size it up against a few other marketplace businesses: Homeaway, Shutterstock and GrubHub.¹ Although they’re different, they’re all participants in some aspect of the freelancer/sharing/independent economy. They all aggregate wildly fragmented markets. They also all make a similar claim: that their platforms ultimately expand the total addressable market and earnings for their merchants, despite acting as a fee taking middleman.To start, here are some high level stats to see how they stack up against Etsy. Note, Homeaway does not report the Gross Values transacted across its platform as much of its revenue comes from subscriptions. I have attempted to back out those numbers based on several assumptions ².

Here are my takeaways from this breakdown:

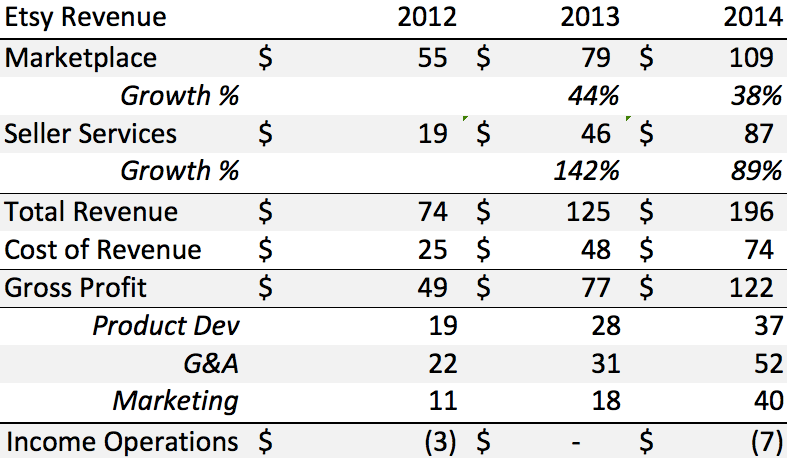

Growth is slowing. This isn’t a huge surprise. It of course becomes incrementally harder to grow at the same Y/Y percentage as scale increases. But it’s especially concerning that their growth slowed in the face of a marketing spend that more than doubled in 2014 from $18 million to $40 million (or, more accurately, increased by 40 percent on a percentage of revenue basis).

Seller services are paramount. Etsy’s gross margin has been increasing by a compounded 10 percent year/year for the past three years. Given that it has a consistent 3.5 percent commission and $0.20/listing fee, the obvious question is how that’s possible? Answer: Ancillary services, add-ons, and products all targeted at its power sellers. Etsy breaks out its revenue into two categories: Marketplace Revenue (3.5% + $0.20/listing) and Seller Services (everything else). At the end of the day, to buy into Etsy, you need to believe that this product-focused revenue will grow significantly and drive its valuation.

Extraordinary network effects. One of my favorite metrics to analyze is marketing spend as a percentage of revenue. In this regard, Etsy is outright compelling. Historically it has spent 40-70 percent less on a percentage basis than their competitors, while realizing similar, if not greater, growth rates than other marketplaces. “Network effects” may be a buzz term, but Etsy is the paradigm. Eighty-seven percent of traffic is direct/organic while 78 percent of purchases are from repeat buyers. There’s a reason they can spend a whole lot less on marketing than the competition: Their powers sellers drive acquisition on their behalf.

Was 2014 an experiment? Etsy will need to credibly communicate to the market that its 2014 marketing efforts were experimental – being the first time its ever ramped marketing efforts so quickly and with a focus on building self-sustaining international markets. Its S1 suggests the increase was mostly buyer-side SEM acquisition in these foreign markets (and research suggests minimal traditional TV or radio advertising). But the results were disconcerting with CAC nearly doubling in 2014.

The strength of the network

When investing in marketplaces, one of the defining factors I look for is evidence that the platform is generating sustainable and beneficial economics on both sides. For example, at Zipments, many couriers are earning nearly double as independent workers on the platform than at their prior messenger agencies.Another example: Bloomnation received the following e-mail from one of its florists:

I wanted to take a moment out of my day to thank you for allowing me to be part of Bloomnation. I spoke to you months ago. I was really hit hard and struggling in Jan-Feb. I was worried being a single mom and this was my 15th year in business. I work alone in order to take care of my son. I had no clue how internet sales worked. Your company has helped me get out of the red zone I was in and revitalize the energy of my shop, flow[ing] with orders. I really really appreciate your orders coming into my shop. In June I was able to put my son into school so I could focus on more business. You helped me fall back in love with my life and love of flowers. I feel so happy its like the feeling of how I first started back in 1999 when I was 19 in my garage on the beach.The reason this supply-side effect matters so much is because of power law distribution: namely, power sellers will be the primary drivers of scale on your platform. While the long-tail of one-off sellers does provide product breadth and liquidity, power sellers will drive both volume and organic referrals to their own native product stores.

Consider how this has played out in the case of Etsy (note that Etsy defines a 2011 Active Seller/Customer to include all 2011 actives, including those acquired between 2005-2010, which self-selects for a large number of existing power users):

In its S1, Etsy offered a glimpse into its 2011 cohorts of both buyers and sellers. In this breakdown, we see that although only 32.3 percent of sellers who had sold an item in 2011 were still actively selling in 2014, those who remained on the platform had developed into serious power sellers – on average $13K per active seller from that cohort. And as power sellers become smarter and empowered by better tools, I expect their average earnings to continue increasing. This is one of the most fundamental signs of Etsy’s strength – the ability for its sellers to earn a living.

On the buyer side, we see an identical pattern of highly valuable repeat purchasing emerge:

Based on what I’ve seen among marketplaces, my best guess is that a typical cohort (2012-2014), will see year/year attrition of 80-85 percent or so, but the business isn’t built on one-time buyers. The power buyers are coming back and purchasing 110 percent year over year. One of the fundamental questions the public markets need to ask is how many of these customers exist in the market and can Etsy find a way to reach them?

But overall, on a high level, Etsy has done an impressive job maximizing value for its sellers, especially as compared to its competitors.

The statistic to look at here is that in spite of active sellers increasing by 63 percent over the past two years, GMS per seller correspondingly increased by 32 percent in the same period. This is in contradistinction to a normal supply/demand curve – and is additional proof that Etsy’s buyers and sellers are among the most loyal and committed.

By comparison, Shutterstock’s active contributors, which also grew by 63 percent in the same period, only saw its earnings per seller increase by 19 percent. Impressive to be sure – but only half of Etsy’s growth.

As an aside, Homeaway would appear to have decelerating value to its property owners. But their business is heavily subscription based and free-to-post listings (implying lower quality properties) are what’s dragging down the averages.

Nevertheless, Etsy and Shutterstock are also effectively free to create profiles and sell goods – whether high quality or not. It’s something I’d consider if I were an investor in Homeaway.

Marketing – CAC and payback

From a pure customer acquisition standpoint, none of these businesses break out CAC or LTV the way traditional e-commerce businesses do. That said, I’ve made some assumptions to get a rough model:

Above, I’ve broken down CAC for buyers OR sellers, assuming the entire marketing spend be allocated to either side. The biggest assumption I’m making in this exercise is simply that I’m defining “new customers” simply by taking the current period’s cumulative buyers (or sellers) and subtracting the prior period’s. That’s obviously a poor assumption because there was (a) attrition among actives and (b) reactivation of dormant accounts. But in assuming that (a) and (b) roughly cancel each other out, we can get a sense of Etsy’s marketing engine.

That said, in reality, Etsy has two customers – buyers and sellers. Its S1 notes “Marketing expenses increased $21.8 million, or 122.2 percent, to $39.7 million in 2014 compared to 2013, primarily as a result of an increase in search engine marketing from Google product listing ads” (implying mostly buyer focused acquisition). So here’s what it looks like if we assume 80 percent of expense on demand-side (buyers) and 20 percent supply-side (sellers).

Overall, CAC increased Q/Q across the board, both for buyers and sellers alike. While worrisome, it’s also expected at Etsy’s scale as there’s a general law of diminishing incremental returns. But here’s why that matters, and how Etsy stacks up versus GrubHub and Shutterstock:

- The glaring metric is how small Etsy’s average spend per buyer and its corresponding Gross Margin per buyer. Etsy is truly only a business that works at scale – which they have – but it’s a clear red flag to other businesses attacking spaces with small order sizes, tiny margins and only medium frequency of purchase. Very few businesses like that will ultimately make it – Etsy did – but it’s the exception: it should be a warning to entrepreneurs.

- The reason GM per customer matters is because customer acquisition is darn hard (and getting incrementally harder) and large order sizes, large margins, or high frequency provide a vital margin of error. Etsy stacks up better than its competitors on Payback period, but its expensive 2014 eroded its Payback advantage.

- Most marketers will tell you that, at Etsy’s scale, targeting a Payback of anything under 12 months is good. And even with its small revenue/buyer, it’s still well below 12 months. But the gap is closing fast. Even with its strong network effects, I fundamentally do not believe its CAC can be reduced significantly, if at all. That leaves two options: 1) Improve gross margin to enhance revenue/buyer or 2) Stop investing as heavily in growth to realize the benefits of its highly profitable, power users.

It’s not all about that base

The common thread across all these marketplaces is the continual move away from a dependency on pure transactional revenue. Here’s how all four consider their revenue breakdown:Etsy has six main revenue sources: 3.5 percent transaction commissions; $0.20 listing fees and seller services; promoted listings; direct checkout; shipping labels; and point of sale payments (like Square Reader).

Homeaway has three main revenue sources: subscription revenue from property owners for bundles of listings which comprises 77 percent of all revenues; 10 percent transaction commissions from pay-per-booking listings; and a variety of ancillary revenue sources such as national and local advertising, property management software solutions, insurance products, and tax preparation services.

GrubHub has two main revenue sources. It’s notoriously tight-lipped regarding its exact commission structure, but most estimates put its base commission to be relevant on listings about 10 percent and variable commission for preferred placement.

Shutterstock has four main revenue sources: subscription purchase packages; on-demand pricing where sellers receive 20-30 percent of the purchase price; license revenue from its video and music assets; and ancillary revenue from its online learning platform SkillFeed or cloud asset management software, WebDAM.

For each of these marketplaces (with the curious exception of Homeaway ³) base transactional fees are of diminishing incremental importance – with ancillary products and services driving much of the platform margin growth. This likely explains why, for example, Grubhub has been so focused on entering the delivery game: a significant gross margin boost.

In Etsy’s case, the growth of non-transactional revenue is their strongest growth driver. So much so that they explicitly highlight the growth in their S1:

Etsy’s Seller Services revenue has nearly doubled from 25 percent to 45 percent of total revenues in the last two years and now includes a full 450bps of Etsy’s gross sales volume. Vitally, the hyper growth in these new categories is offsetting a tangible decrease in Etsy’s core marketplace gross margin – down 8 percent over the past two years – most likely from discounting to new customers which has a contra-revenue (and thereby margin-contracting) effect.

These Seller Services are doubly important because Etsy also covers credit card processing fees on marketplace transactions, cutting its marketplace GM from 5.65 percent to an effective 3.5-4 percent. With that in mind, the question investors should be asking is how expensive are these supplementary services to build and operate and can they continue to grow nearly 100 percent year over year?

Although 2014 revenue grew by 57 percent, overall expenses grew by 68 percent. The silver lining is that if you remove marketing expense from the calculation, annual expenses grew only 51 percent.

Investors should be pushing Etsy to break out these expenses more clearly. Last year was one of learning on the marketing side for Etsy, and I would expect performance and spend to stabilize in 2015. If that assumption is correct and if the expenses requisite to support seller services continue to mature, Etsy will have a healthy balance sheet – although, at the expense of hyper growth.

Isn’t crafting trendy?

Both GrubHub and Shutterstock go to great lengths to define the breadth of their space – $70 billion and $16 billion, respectively – with Shutterstock even commissioning a research report on the study. The home vacation rental market is massive, easily bursting into the hundred-plus-billion mark. But Etsy makes no mention of its market size – no comparison to arts and crafts supplies (a $30 billion annual segment). It’s a curiosity that reflects Etsy’s possible Achilles heel – that the market simply isn’t that big. It really feels intentionally omitted:Etsy sellers offer goods in dozens of online retail categories, including jewelry, stationery, clothing, home goods, craft supplies and vintage items. Euromonitor, a consumer market research company, estimated that the global online retail market was $695 billion in 2013, up from $280 billion in 2008, representing a compound annual growth rate, or CAGR, of 19.9%. This growth is expected to continue, with the global online retail market becoming a significantly larger portion of the total retail market, reaching $1.5 trillion by 2018, implying a 16.6% CAGR from 2013.With GrubHub at 2 percent market penetration and Shutterstock at (estimated) 2.5 percent if Etsy is nearing 10 percent of its addressable market, for example, that would certainly explain why its growth is slowing while GrubHub is accelerating in spite of identical gross sales.

While, in principle, the market for jewelry, home goods and craft goods is outright massive, Etsy’s strict guidelines around hand-crafted, artisanal products is certainly limiting. This concern that led to its major revision of seller guidelines 16 months ago as well as its launch of Etsy Wholesale just 9 months ago. Even so, the success of outsourced vendors has yet to be validated – and casts real concern around their total addressable market.

Running through this market size exercise would make me extremely wary as an early-stage investor of the myriad niche or vertical specific marketplaces targeting smaller markets. I’d go so far as to say that any space without a minimum of $5 billion in annual transaction volume is a non-starter.

The bet

If Etsy were to hit the public markets today at a $2 billion valuation (WSJ says $1.7 billion) here’s how it would compare to its peers:

On both a revenue and EBITDA basis, Etsy believes it deserves a premium to more mature, slower growing marketplaces, which is fair. But unlike GrubHub, its growth is decelerating – quickly – even in spite of its focused efforts to leverage high-volume whole sellers and point-of-sale.

The bet on Etsy is:

- The market is ultimately larger than we currently estimate, especially internationally. Because GMS growth is decelerating by 15-30 percent annually, you need to either believe that macro trends cause consumers to increasingly favor hand-made artisanal goods, or that they’re able to appeal to the non-handmade, non-artisanal yet “still boutique” buyer and seller.

- Etsy can continue to acquire and cultivate power users via low-cost marketing through the power of its community and network effects.

- They can continue to build and launch high quality ancillary products that an overwhelming percentage of their active sellers are willing to pay for (between 18-36 percent of all active Etsy sellers currently subscribe to each of their Seller Services) – thereby enhancing their overall Gross Margin.

- It’s able to build product and sustain community quality while simultaneously stabilizing (or contracting) overhead expenses.

- Their community and brand values render them not susceptible to even more niche/verticalized platforms such as Minted or Dawanda stealing ever precious market share.

Some parting notes

As Bill Gurley wisely communicated to Uber, one of the best ways for a company to avoid disruption is via cutting prices to the point where its effectively impossible to be undercut on price. This is Etsy. As compared to its peers, Etsy is the cheapest of transactional marketplaces for both buyers and sellers. But that comes at a cost: Etsy only works at scale – and its profitability is thereby dependent on non-transactional revenue.Investors should be confident that Etsy’s loyal community will continue driving sales into the foreseeable future. The converse is that GrubHub or Shutterstock’s merchants are far more likely to abandon the platform for a lower-cost provider. Taking into account the size of the space and GrubHub’s growing margins, it’s no wonder investors are so bullish on the next generation of food-delivery apps – Postmates, Doordash and Sprig – with both a huge whitespace and opportunity to steal market share on price.

The majority of marketplace startups today are geo-focused, on-demand platforms (Uber is the paradigm). Though not a single one of these is yet to hit the public markets (or disclose detailed info), there are a couple of clear best-in-class benchmarks already emerging:

- 10x Growers: This has most frequently been going from $10 million in revenue to $100 million in revenue in a single 12-month period (Instacart, Postmates, BlueApron TheRealReal… Uber is of course in a separate orbit altogether) and

- $100k in 30 Days: When platforms are able to launch new cities and see a minimum of $100K in localized GMV in its first month. This new class of marketplaces needs to be highly attuned to unit economics as logistics/delivery charges can handicap otherwise healthy margins.

Appendix

¹ I’ve seen some other articles try to compare Etsy to eBay, Alibaba, Wayfair and Zulily. I think all these comparisons are really flawed. Ebay is far too mature, founded nearly a decade before Etsy, not to mention that PayPal, not its marketplace, is its strongest product. Alibaba is far too horizontal to be an accurate comparison; and although Wayfair and Zulily connect buyers to sellers, they’re both predominantly flash sales e-commerce businesses. I concede that the actual Wayfair platform is functionally a marketplace, but its growth driver, Joss & Main, does not conform to the same dynamics.

² Homeaway’s pay-for-performance listings generate a 10 percent transaction fee. They have a variety of subscription bundles for power sellers, but we can assume that power sellers are savvy enough to generate noticeable discounts to that 10 percent fee on a subscription basis. I used a sliding scale, based on their subscription versus pay-for-performance listing to estimate their Gross Margin. Their Gross Margin was also positively affected by ancillary services (which they do self report). Shutterstock does not formally note their GMV or Gross Margin but it can be backed out by assuming that their revenue represents gross transactional revenue, and subtracting the payouts to contributors noted in their cost of revenue description. Although that take is approximately 70 percent, their gross margins are ultimately slightly higher due to revenue from the SkillFeed platform and WebDAMs software.

³ I can only assume in order to mitigate questions of relevance versus Airbnb’s low friction signup/transactions. As well as to increase Gross Margins – I estimate from ~5% effective on a subscription basis closer to 10%. That said, their subscriber services are one of their strongest differentiators relative to Airbnb and it will be interesting to watch that battle play out.

Author note: I am not a registered investment advisor not am I a public market expert. This post should not be the basis of your investment decisions.