Editor’s note: Bill Maris is president and managing partner at Google Ventures.

Editor’s note: Bill Maris is president and managing partner at Google Ventures.

I’ve heard people wonder if we’re in a bubble with regard

to startups. Is it as bad as the 2000 dot-com bubble? Might it actually

be worse? I thought it would be worthwhile to look at the available data

to see if we can figure this out with more than just a personal

opinion. So I asked our engineering team at Google Ventures to dig into

the bubble question and find out what the data say. In this post, I’ll

share what I learned.

Back in the late 1990s, venture capitalists got very

excited about the Internet. A whole lot of money was poured into some

companies that failed rather spectacularly, and a lot of people lost a

lot of money.

Fast forward to 2015. If you read the headlines

about multi-billion-dollar valuations for companies like Uber (one of

our portfolio companies), Airbnb and Dropbox, it’s easy to see why some

people are feeling antsy. Is everyone irrationally excited about new

platforms and economic models in the same way folks were excited in

1999? Or is this different? There are two sides to the case.

The case against a bubble

While the data show that venture investing is increasing, they also illustrate four key differences from the dot-com bubble.

1. Companies are slower to go public

During the 2000 bubble, many companies rushed to go public

before they had any revenue. Today, companies are taking longer to IPO:

In 2000, money flooded into venture capital, and VCs used

that money to fund companies that might not otherwise “meet the bar” —

resulting in some spectacular failures. Today, VC fundraising is on the

uptick, but it’s still far below the 2000 level:

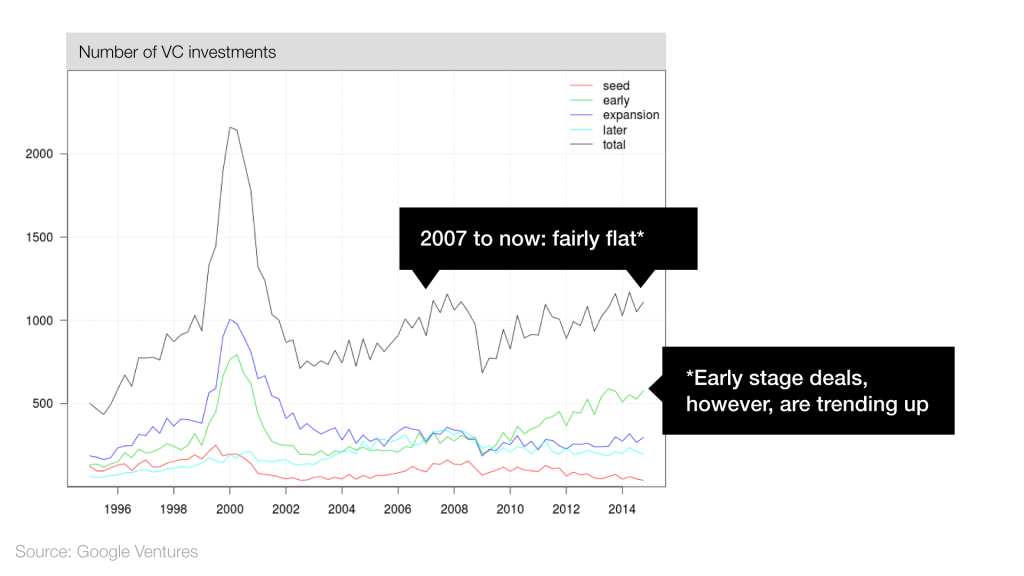

In 2000, VCs made a record number of investments — over

2,000 that year alone. How does that compare to today? It may not feel

like it, but the number of VC investments has actually been fairly flat

since 2007. This suggests that VCs are still being selective:

Venture capital investing shot up in 2013 and 2014, but it’s still far short of dot-com bubble levels:

During the bubble in 2000, more VC dollars led to more

investments. Today, VC investing is up, but the number of deals is flat.

What’s going on? As we’ll see, investors are focusing their money on a

relatively small number of large deals.

The case for a bubble

Our data analysis reveals more than sunshine and lollipops.

Here are six troubling signs that suggest we may be in another tech

bubble.

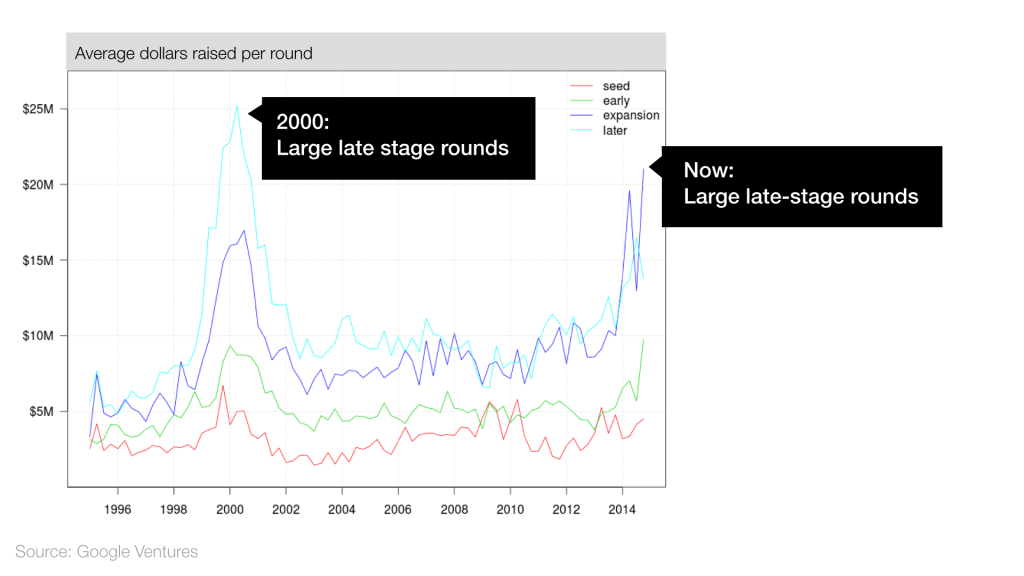

1. Investors are putting more money into late-stage rounds

If you believe late-stage financing is replacing IPOs for

fundraising, this might not be a worrisome sign. Still, it’s easy to see

the similarity to 2000:

Until now, our data have shown an environment that is milder than 2000. Today’s valuations tell a different story:

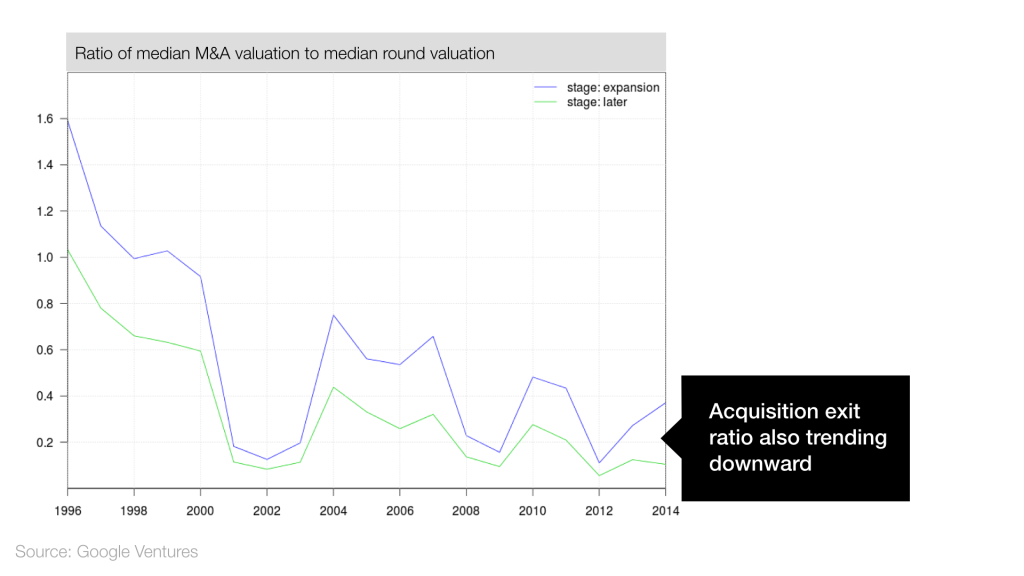

Here’s another concerning chart:

IPO valuations have increased across the board, but the

most successful companies are going public at much higher valuations (or

perhaps they’re just waiting longer).

Both late-stage valuations and acquisition price tags are

going up. Meanwhile, IPO valuations are going down. Late-stage financing

and acquisitions are, in effect, replacing IPOs.

The data indicate that IPO valuations are not growing as

fast as late-stage private company valuations. In fact, if we look at

the ratio of IPO valuation to late-stage valuation, we can see that this

ratio has been declining since 2009. This suggests that late-stage

investors might expect lower returns than in the past.

The data clearly show an increase in late-stage financing,

but there are a couple ways to interpret this. One hypothesis is that

plentiful late-stage financing from VCs and private-equity funds is

causing companies to stay private instead of going public or being

acquired. Another take is that technology has enabled companies to grow

more quickly, and late-stage funding has risen to meet the needs of

these young (but large) startups.

The bottom line? If there is a bubble, it’s a different

kind of bubble. And this makes sense, because the market and technology

landscapes have changed dramatically in the last 15 years.

Of course, companies will still fail, and with today’s huge

valuations and the accompanying attention, those failures will seem

even bigger and splashier. But that doesn’t mean the sky is falling.

When one of these super-valued companies fails — which is inevitable —

we’ll have to take a deep breath and ask ourselves whether it’s

something endemic or just part of the normal failure rate. Perhaps we

should look at the data before pressing the panic button.