“I hope we put ourselves out of business,” said Charlie Smith, the

pseudonymous head of Great Fire. And he was serious. After all this

Chinese Internet monitoring watchdog GreatFire.org is no ordinary case.

“I hope we put ourselves out of business,” said Charlie Smith, the

pseudonymous head of Great Fire. And he was serious. After all this

Chinese Internet monitoring watchdog GreatFire.org is no ordinary case.Started in 2011 by three anonymous individuals tired of China’s approach to the internet, it initially tracked the effects of the country’s censorship system on websites. Over time, it has risen to become perhaps the most trusted authority on the subject.

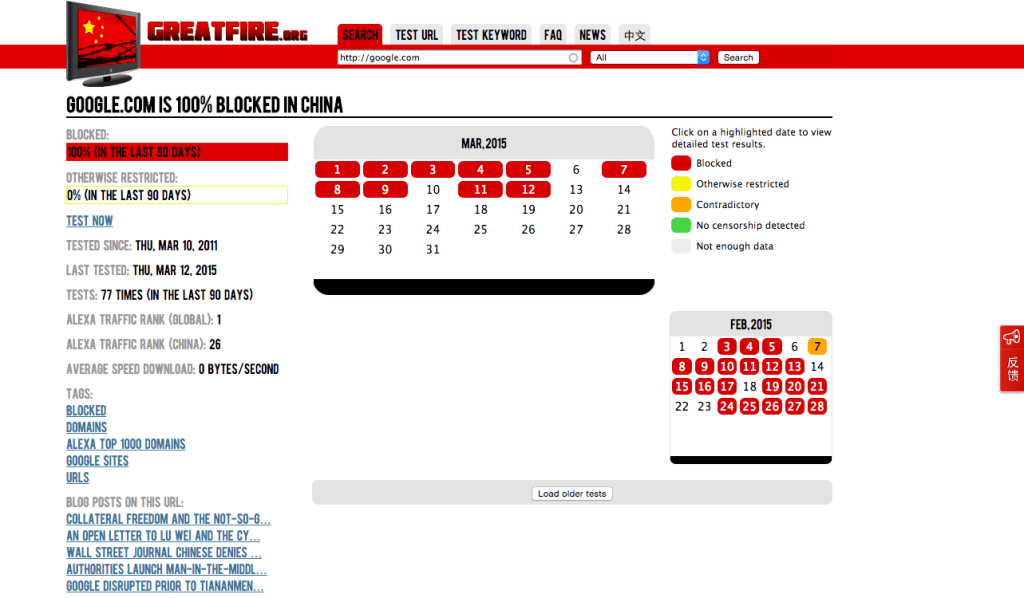

The Great Fire site itself is censorship database. Visitors to input a URL to determine if the website is blocked in China. It is available in English and Chinese, and periodically tests its collection of over 100,000 URLs to produce a history of the availability/restriction for each one. A hugely useful resource in its own right, GreatFire has come to mean a lot more than just checks. These days, the three founders document new instances of internet restrictions and foul play in China via the organization’s blog and @greatfirechina Twitter account.

Great Fire regularly referenced by Reuters, The Guardian, Wall Street Journal, Bloomberg and other global media — including TechCrunch, of course. Stories it has dug up have included apparent attacks on Apple’s iCloud service, the blocking of Instragram and messaging apps, restrictions on Google services (of course) and — most recently — details of a man-in-the-middle attack on Microsoft Outlook users in China.

That’s made the site — and its founders — a go-to resource for media, activists and anyone with an interest in the internet in China.

“In terms of blogging, we’ve amazed ourselves,” said Smith. Smith highlighted the recent Microsoft attack and the role that Great Fire played publicizing it.

The story began like many others with a post on the Great Fire blog. That was picked up by media which gave the finding a global platform and attention. Microsoft entered the scene when it confirmed that “a small number of customers [were] impacted by malicious routing to a server impersonating Outlook.com” — and suddenly what was initially a small discovery had become a topic in media across the world, China included.

“It got me thinking, if we weren’t around who would’ve exposed that? It’s a serious thing,” Smith said.

Collateral Freedom

Great Fire is an invaluable resource for Asia-based tech reporters, but blogging and retroactively documented censorship isn’t going to down the Great Firewall, as China’s internet censorship organ is known. For that, Smith and his fellow vigilantes have a more sophisticated plan of action that they call ‘Collateral Freedom’. It’s a concept that leverages cloud-based content networks to give blocked websites and services a new, unblocked lease of life in China.Hosting a website on a service like Amazon Web Services (AWS) or Alibaba’s Aliyun cloud — Smith declined to say which services are used, but he did confirm that it is not reliant on a single vendor — is designed to make the decision to block it more complicated. While we don’t know the ins and outs of how China determines which websites to block, it is seemingly able to do so nearly at whim. Collateral Freedom adds a new layer of decision making because it theoretically forces authorities to block all sites on the cloud service if they want to ban the contentious material in question. So, if Collateral Freedom is used to host a Google.com mirror on AWS, for example, a decision to block it will knock out other services that use AWS in China.

Great Fire is betting that China realizes that bringing down massive content delivery networks is not sensible, particularly when companies rely on them for staging websites and services, not to mention conducting business in the country generally.

“Collateral Freedom ties access to information to the Chinese economy,” Smith explained. “If [authorities] truly want to block access to this information, then they must give up certain access to economic freedoms.”

The government has taken action against many services used by Western businesses in China, including Google services, VPN providers and — most recently — popular security software service Avast. Smith previously told us that censorship had “become a serious business issue,” and Great Fire’s Collateral Freedom theory works on the basis that blocking companies that provide the internet plumbing is a step too far — but, even if the hammer did fall on them, the resulting outcry would cause significant harm for China because it would raise awareness of censorship issues in the open, Smith argued.

“It’s going to be very difficult to block [Collateral Freedom sites] without causing a lot of economic damage. We just need more critical mass in terms of partners,” he added. “And we are also open sourcing the code so that people will be able to go and do it themselves.”

Overseas Efforts

A new push to internationalize its efforts began this month, when Great Fire partnered with Reporters Without Borders to ‘unblock’ nine websites across 11 countries, including Russia and China. Great Fire previously considered expanding its efforts into other censorship affected countries, but instead it chose to open-source the basics for others to run with the ball. This allows its small team of volunteers to focus their efforts on China.Collateral Freedom isn’t just about making websites accessible. Great Fire has released an Android app that uses the system to grant users access to blocked websites inside China without a VPN. We’ve confirmed with multiple contacts in China that the browser can be used to access Facebook, Twitter and other censored sites using a Chinese service provider.

The organization also runs Free Weibo, a firehose-like service that shows all messages posted to Weibo, bypassing the heavy censorship filter that its users on the service are typically subject to. Free Weibo is available on the web and via an Android app, Apple removed the iOS app from the App Store last year. The incident is a sour one for Great Fire, which maintains that the U.S. company acted on instructions from the government, thereby tacitly endorsing internet censorship. (That’s opposed to the likes of Google, Facebook and Twitter all of which have all been vocal opponents.)

It’s still early days for Collateral Freedom, and China’s response to the initiative isn’t yet clear. Authorities did make one drastic move to block a major content delivery networks that Collateral Freedom relies on. Verizon-owned Edgecast was blocked back in November, knocking out thousands of websites from China’s internet space in the process. Despite that, the Great Fire team claimed that China has not yet fully cracked down on its initiative, and they believe that is a positive sign.

“The authorities have tried to stop our services by disrupting CDNs, but, apart from one, have stopped short of outright blocking them. Recognizing that the authorities have been hesitant to crackdown on our method of circumvention, we have accelerated our expansion of the development of Collateral Freedom,” the organization said in a blog post.

Painted As Agitators

All three Great Fire founders have regular day jobs, which is pretty insane considering that their side project is devoted to tackling the world’s most prominent internet censorship regime. Clearly, then, their efforts require outside funding; Smith declined to reveal details of Great Fire’s backers, only than that “people have supported us, a lot [of whom are] inside China.”“We are funded by organizations that support a free Internet, in China and beyond,” Great Fire says on its website. The organization’s advisory board includes former CNN journalist and Global Voices founder Rebecca MacKinnon, high profile Chinese blogger Isaac Mao, and James Vasile of the Open Internet Tools Project and the Software Freedom Law Center.

Since its inception in 2011, Great Fire has been a dogged and persistent critic of China, but it appeared to reach a milestone this January when it was acknowledged by the government for the first time.

Speaking to state media following the emergence of information regarding the attack on Outlook users, Jiang Jun, a member of the the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC) which manages the internet in China, accused Great Fire of being “an anti-China website set up by an overseas anti-China organization.”

Jiang claimed the organization had timed its disclosure to coincide with a clean up of ‘harmful’ social media accounts on Weibo and popular messaging app WeChat. Great Fire’s goal was “aiming to incite dissatisfaction and to smear China’s cyberspace management system,” the official argued.

Great Fire hit back with an open letter to the head of the CAC. “We are not anti-China but we are anti-censorship in China,” the founders explained, and Smith echoed those comments to TechCrunch.

“We [three] all have close relations with China; we’re invested in this country — I love the place, we all love the place,” he said.

“We can be against the censorship and love the country… we don’t like it when they paint us in that manner,” he added. Later, however, he admitted that being called out in the media — Great Fire was mentioned on websites and video broadcasts in China — was actually a badge of honor, and a sign that the discussion around censorship is advancing.

Nonetheless, with the overall objective so high, this is not a relaxing side-project for the founding team.

“It’s really a full-time project [and] emotionally it can be difficult,” Smith explained. “It is not something I can talk about over beers with friends, for example.”

As projects in the tech industry go, it doesn’t get more audacious or ambitious than Great Fire. That underdog or ‘David versus Goliath’ challenge makes you naturally root for the three founders, particularly given the merits of their ultimate goal to remove China’s internet blinkers.